Concentration in the context of foreign trade can be characterized with the relatively larger share of subgroups with respect to product mix, economic activities and destination countries. Recent studies in the literature suggest that the tendency to concentrate on certain groups in exports may lead to volatility regarding terms of trade and also amplify the impact of global shocks on the domestic macroeconomic outlook through the trade channel (Jansen, 2004; Romeu and da Costa Neto, 2011). This phenomenon is observable in cases where the foreign trade is structurally concentrated on certain product groups, particularly in commodity-exporting and/or open emerging economies. It increases the macroeconomic uncertainty, reduces investments, and puts a downward pressure on the long-term growth performance (Hesse, 2008). As a matter of fact, theoretical and empirical studies in the literature point to the positive impact of export diversification on economic growth and productivity (Hausmann, Hwang and Rodrik, 2006; Hausmann and Klinger, 2006; Feenstra and Kee, 2008).

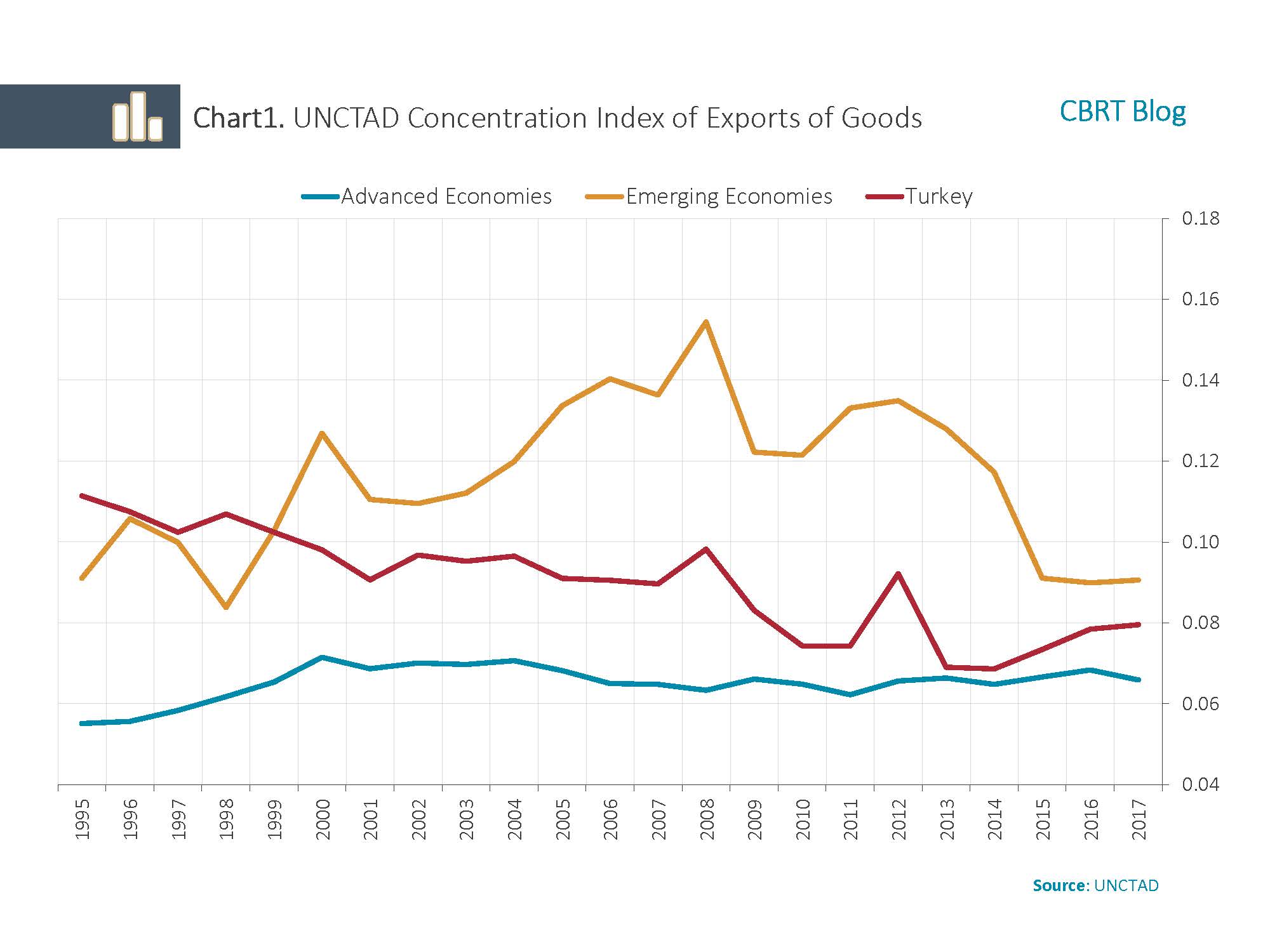

United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) constructs indices to measure the cross-country concentration and diversification of exports of goods. A historical analysis of indicators in the UNCTAD concentration index suggests that the emerging economies (EM) opted for diversification in exports of goods, particularly following the global financial crisis (Chart 1). In this context, the trend in these countries differs positively from the advanced economies group that did not display a noticeable change in export diversification. In addition to quantity diversification and enhanced quality, improvements in areas such as financial deepening, infrastructure investments, institutional structure and protectionist measures in foreign trade stand out as factors supporting export diversification in EMs on a historical basis. Meanwhile, with regard to the level, the degree of diversification in advanced economies proves much higher than emerging economies. Turkey performs better than the average of emerging economies in terms of the respective index (Chart 1).

This study examines whether the diversification trend across the EMs is also experienced in Turkey. Accordingly, high frequency indicators are derived to facilitate the detailed measuring and timely monitoring of the degree of diversification in Turkish exports in various classifications[1]. Through the Concentration Ratio (CR) and Hall-Tideman index (HTI) indicators, the degree of foreign trade diversification for country, product and economic activity subgroups was measured on a monthly basis for the 2003-2018 period[2]. The decline in the values of both indicators points out that concentration in exports decreased, whereas diversification therein increased across subgroups[3].

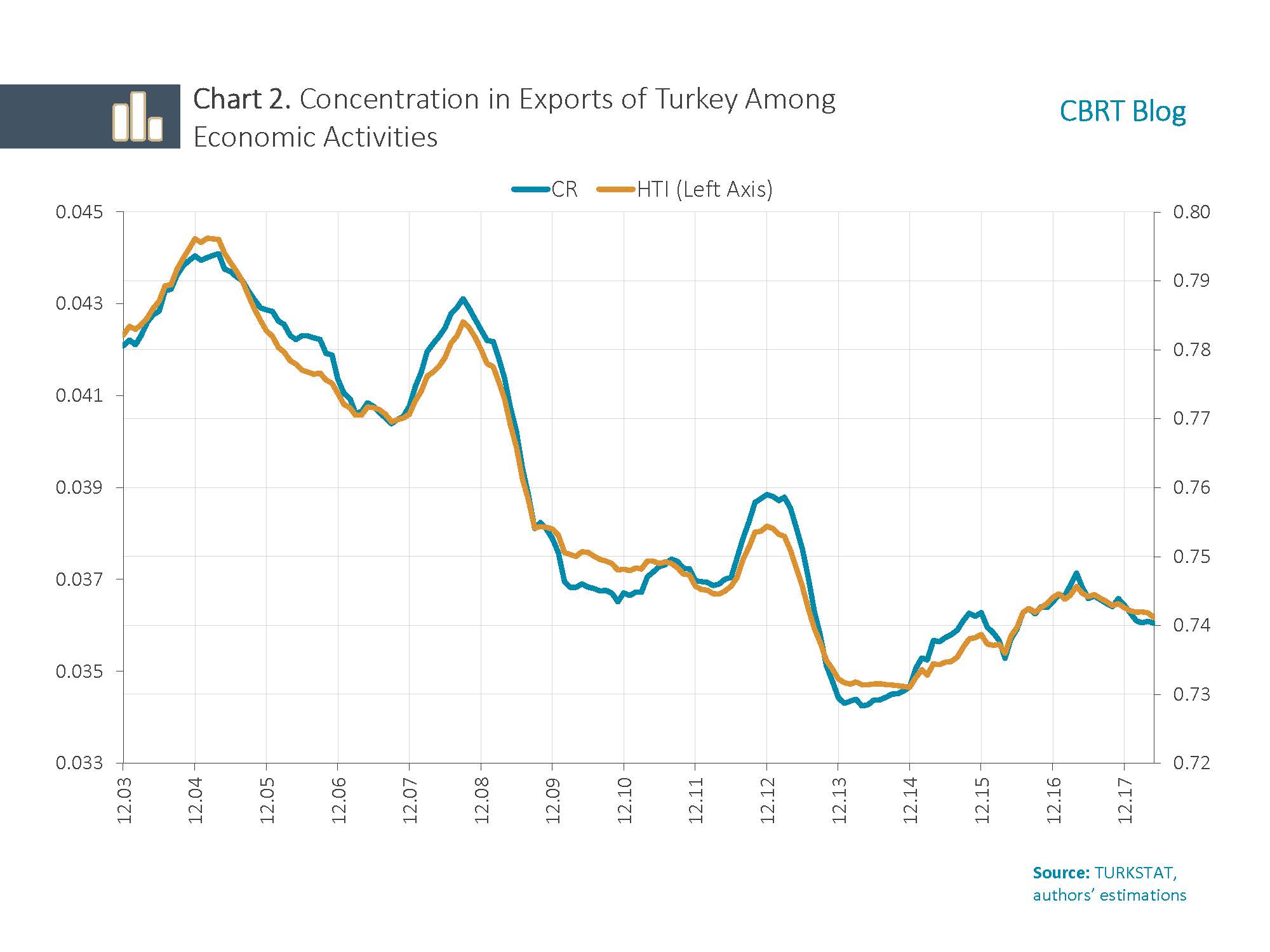

In terms of economic activities, these indicators were estimated for 102 subgroups to measure diversification in ISIC-Rev4 classifications. Subgroups cover a broad range of areas of economic activity such as the manufacturing industry, agricultural production and services. Overall, results point out that over the examined period, diversification increased excepting for cyclical movements in terms of economic activity groups (Chart 2). Having maintained the pace of decline until 2014, index results followed a flat course following that period. Moreover, results of analysis further indicate that the number of economic activity groups with a low share of exports declined, whereas an activity-based overall growth was recorded in Turkey’s exports. The share of economic activities related to the textiles sector which has a high share in Turkey’s exports (such as manufacturing of clothing and wearing apparel, weaving and crochet products and other textile products) saw a decline in the analyzed period, while the share of a wide scope of economic activity groups related to the manufacturing industry in the composition of exports (motor vehicles, manufacturing of general purpose machines, furniture and basic chemicals) registered significant increases.

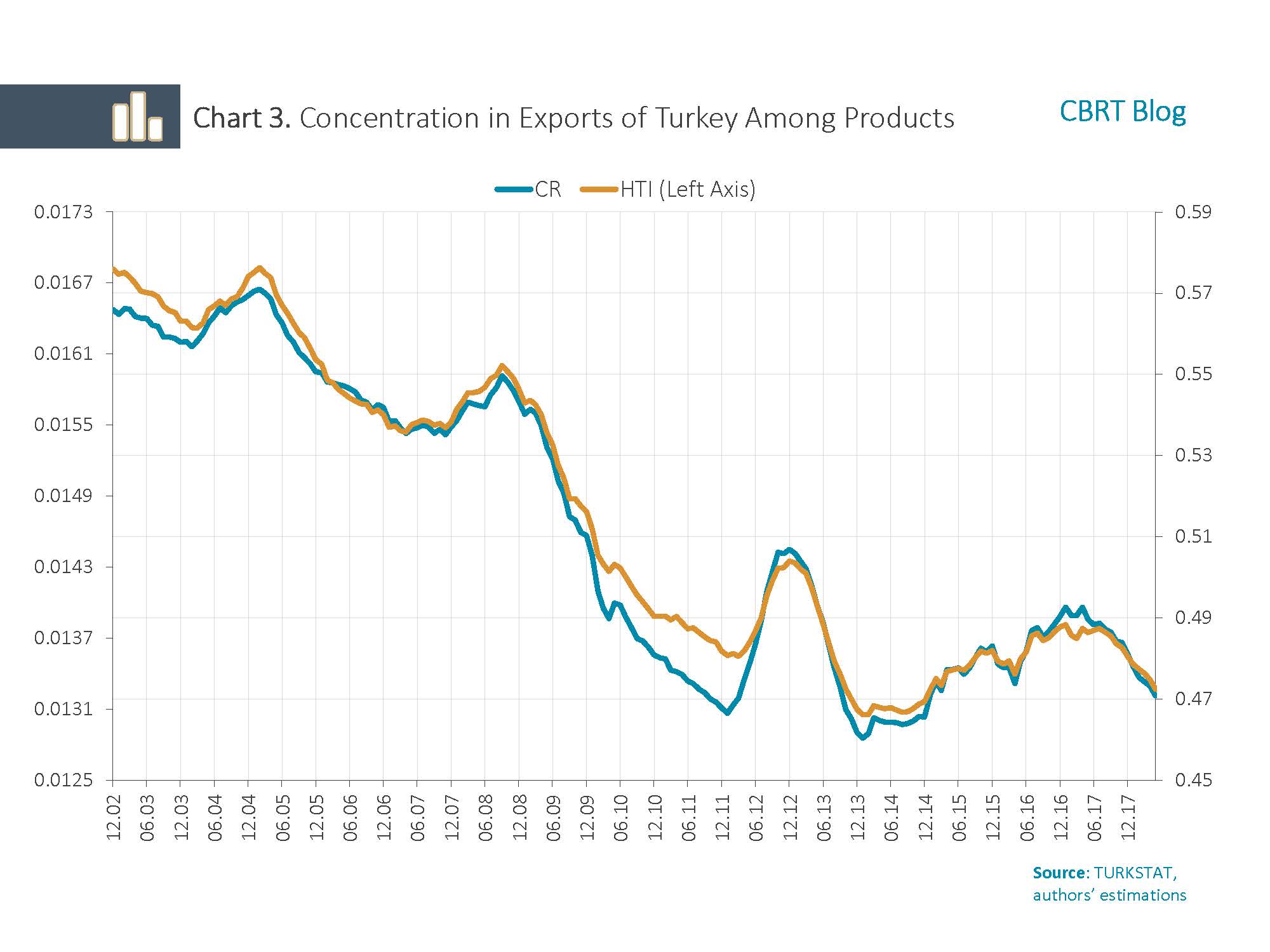

In addition to the activity group, analyses were also repeated on a product basis. CR and HTI indicators were estimated for 264 sub-items under the STIC-Rev4 classification. The general trend exhibits a diminished concentration in exports across products, yet this trend flattened in the last couple of years (Chart 3). The structural change in the form of a decline in the contribution to total exports by groups with low share regarding economic activity also applied to export developments across product mix.

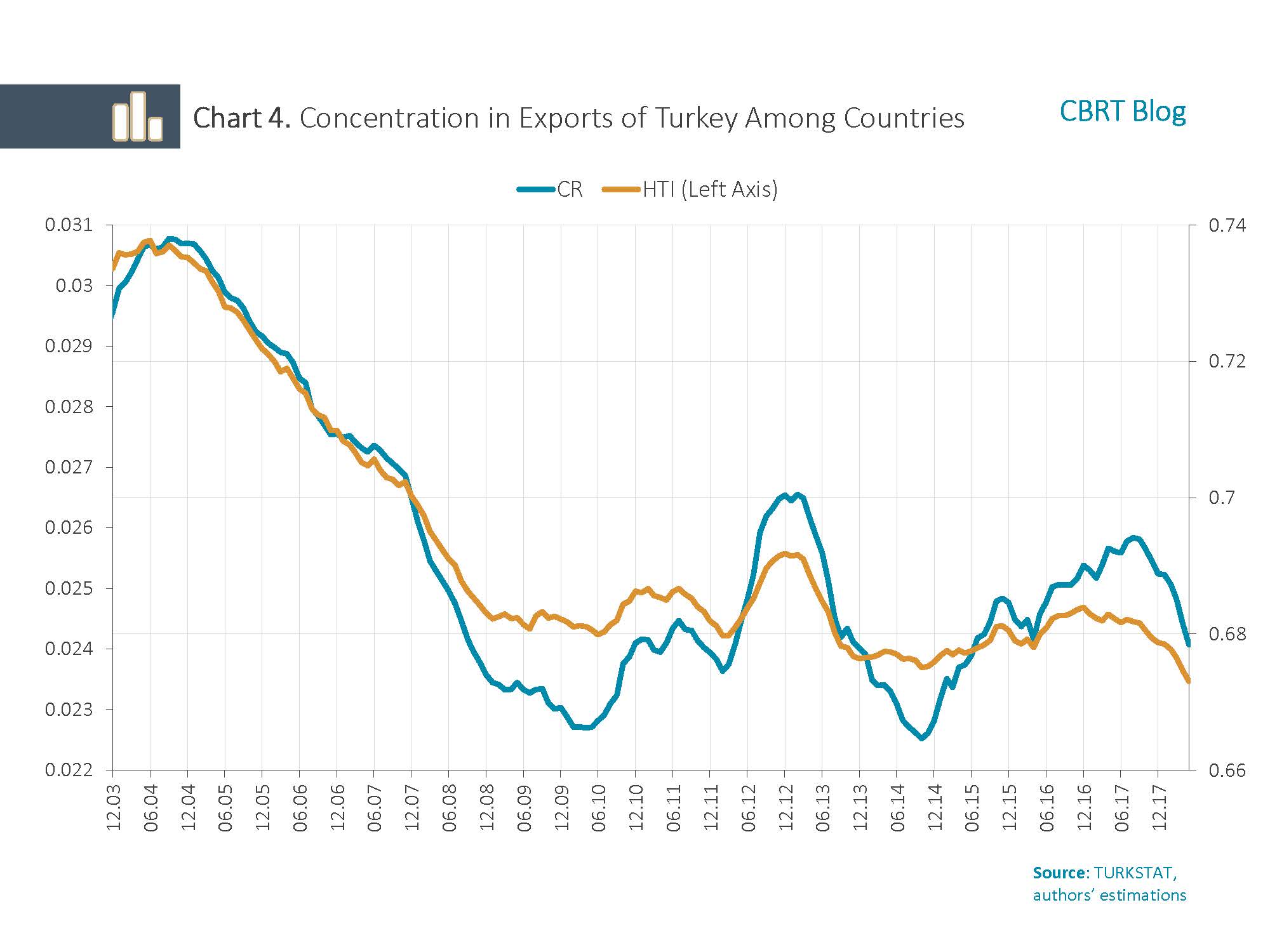

As the last analysis, export developments were examined on a country basis. CR and HTI indicators estimated through the shares of 217 countries in Turkish exports are displayed in Chart 4. Country-based concentration got steadily lower until the period of global crisis, and exports to countries other than the main export group recorded an increase, whereas a fluctuating course was seen following this period.

All in all, product, activity and country-based diversification in the Turkish foreign trade witnessed a significant upswing in the last 15 years. On the other hand, diversification has come to a halt in recent years. In this context, steps to be taken to improve diversification in exports are considered vital. It is projected that practices such as selective loan arrangements, hedging methods and project-based incentives that will help exporting sectors access financing and carry out risk management will underpin export diversification. Moreover, factors of structural quality such as fostering foreign trade in local currencies and sustaining the market shifting flexibility of exporters are also believed to contribute positively to diversification and also act to lower the economic fragility. These developments are thought to play a key role in limiting the negative repercussions of increased protectionism in foreign trade on local macroeconomic outlook.

[1] Definitions and information regarding common indicators used in measuring the degree of diversification in literature is given in Meilak (2008).

[2] Estimations of the shares of subgroups within total exports were based on 12-month cumulative values denominated in USD.

[3] In the HTI index, the share of each category in total exports was weighted by multiplying the relative status of the respective group within all groups. The HTI index is sensitive to the changes in groups with relatively low shares. Details for the index construction method are given in Hall and Tideman (1967). The CR index was estimated as the share of 20 categories with the highest share in total exports. The CR index is sensitive to the changes exclusively in categories with relatively high share.

References

Feenstra, R., & Kee, H. L. (2008). Export variety and country productivity: Estimating the monopolistic competition model with endogenous productivity. Journal of International Economics, 74(2), 500-518.

Hall, M., & Tideman, N. (1967). Measures of concentration. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 62(317), 162-168.

Hausmann, R., Hwang, J., & Rodrik, D. (2006). What you export matters. Journal of Economic Growth, 12(1), 1-25.

Hausmann, R., & Klinger, B. (2006). The evolution of comparative advantage: The impact of the structure of the product space. Center for International Development and Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University.

Hesse, H. (2008). Export diversification and economic growth. Commission on Growth and Development working paper; no. 21. World Bank.

Jansen, M. (2004). Income volatility in small and developing economies: Export concentration matters (No. 3). WTO Discussion Paper.

Meilak, C. (2008). Measuring export concentration: The implications for small states. Bank of Valletta Review, 37, 35-48.

Romeu, R., & da Costa Neto, M. N. C. (2011). Did export diversification soften the impact of the global financial crisis? (No. 11-99). International Monetary Fund.