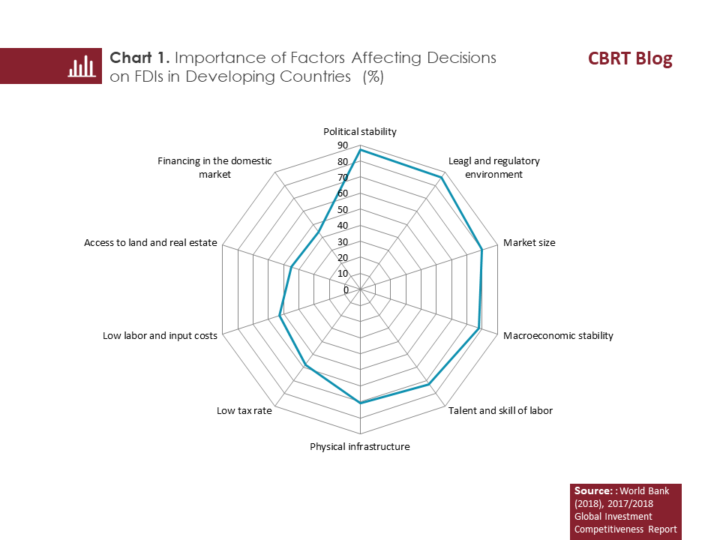

According to the report by the World Bank (WB), the search for market and efficiency is the major factor leading investors to invest in different countries.[1] Chart 1 demonstrates the factors affecting the decisions on foreign direct investment (FDI) in developing countries derived from the results of the survey in the WB report.

Investors seek political stability, transparency and predictability in the conduct of public policies, and a favorable investment climate (investment protection guarantees, ease of starting a business, investment incentives, etc.), in that order of importance. As the search for efficiency in production increases, the importance of factors such as low costs of labor and labor talent and skill, good physical infrastructure, macroeconomic stability, favorable exchange rate, low tax rates, and low cost of inputs also increases. Countries that pursue business-friendly policies and efficient procedures related to business establishment, and that are able to build strong contractual linkages with local suppliers have precedence.[2]

Recent FDI Developments in Turkey

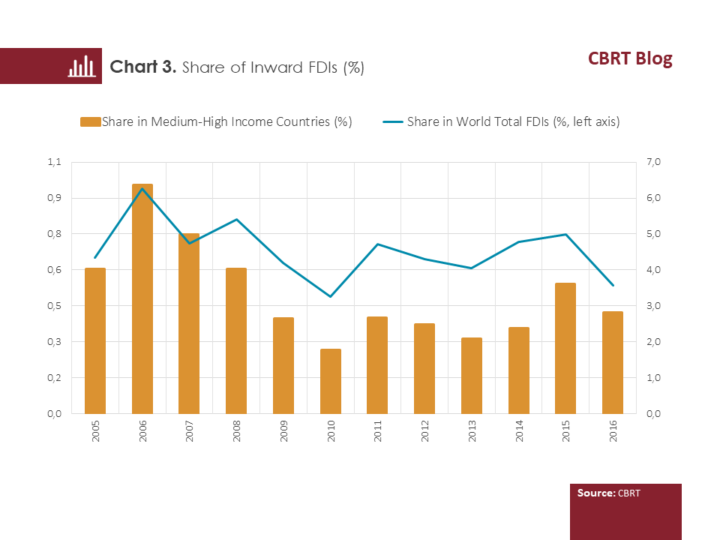

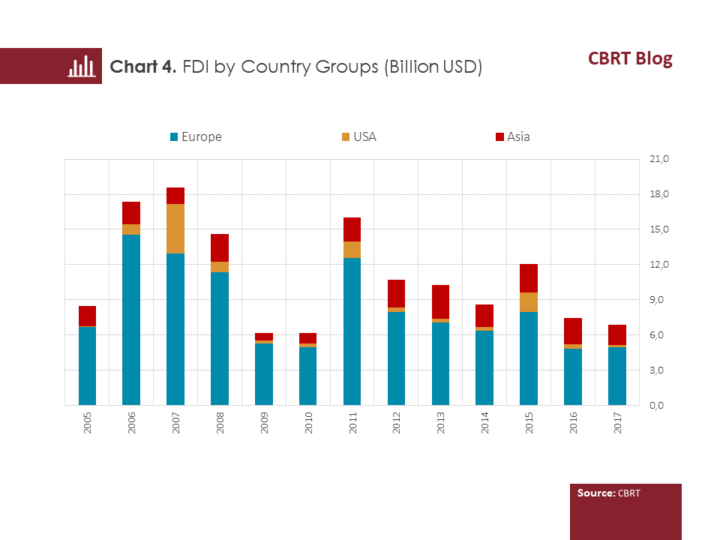

Capital inflows to Turkey visibly increased after 2005.[3] The number of companies with foreign capital rose to 58 thousand in 2017 from approximately 15 thousand in 2006. The ratio of FDI inflows to GDP was close to 3 percent in the 2006-2008 period of relatively intense privatizations but dropped to 1.5 percent after the global financial crisis (Chart 2). Turkey attracted 3 percent of total FDIs in WB-defined middle- and high-income group countries, which also include Turkey, in the aftermath of the crisis (Chart 3). The majority of investments come from European countries but the share of Asian countries has also grown in the post-2009 period (Chart 4).

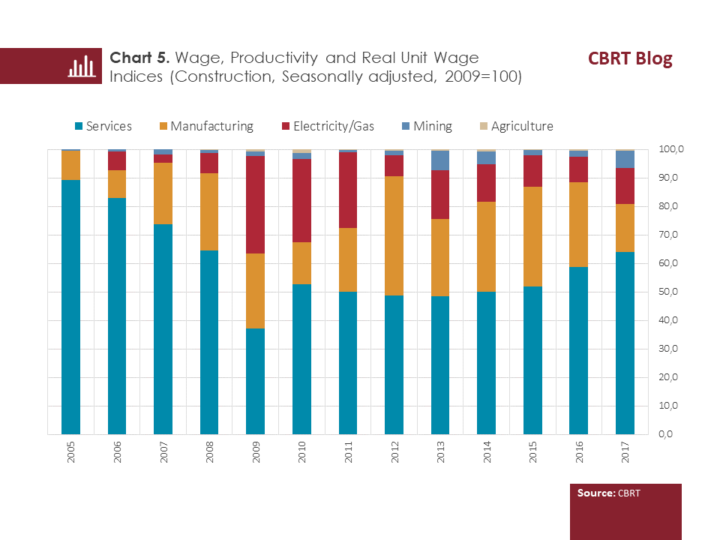

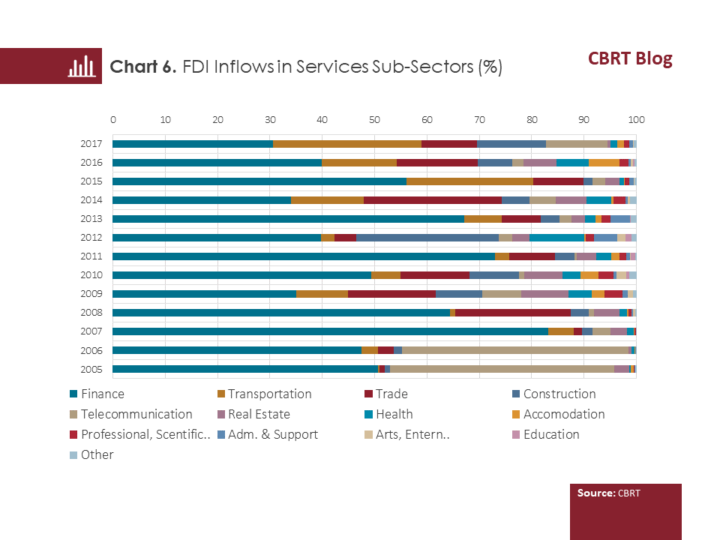

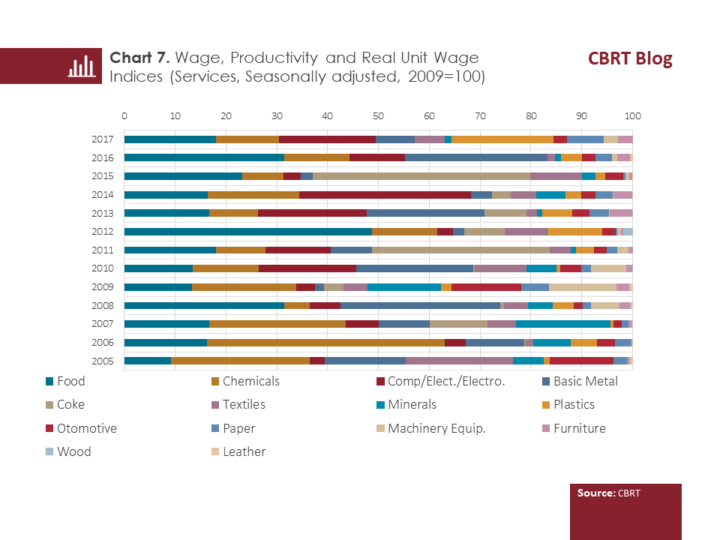

The share of the services sector in FDIs, which had increased until the global crisis in 2008, decreased afterwards due to privatizations in the manufacturing industry and electricity/gas sectors (Chart 5). In a breakdown by services sub-sectors, FDIs in the information sector declined in the post-crisis period whereas FDIs in construction and transport sectors rose (Chart 6). As for the manufacturing industry, food, chemicals and chemical products, and basic metal groups had a large weight across all periods while electricity and petroleum sectors also registered inflows in the post-crisis period (Chart 7).

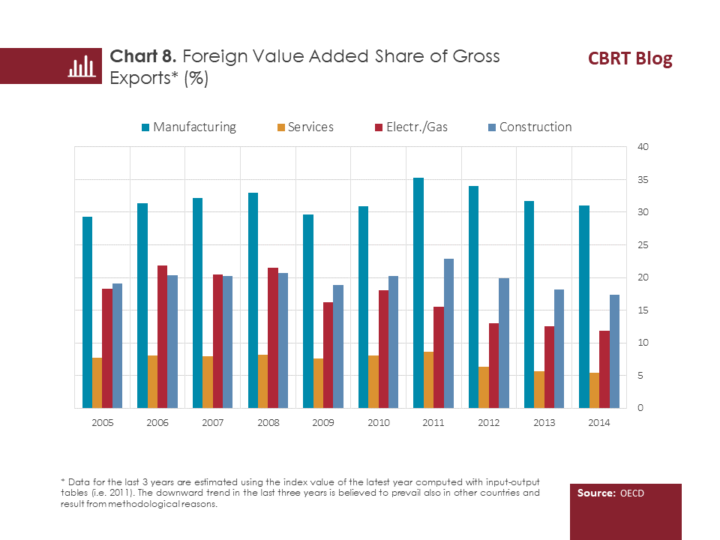

Chart 8 shows the foreign value added share of gross exports, which is one of the global production chain indicators in the economic literature computed using international input-output tables. The rate of integration to global production chains in the manufacturing industry is well above that in other sectors: foreign investments in the manufacturing industry are performed by efficiency-seeking firms as part of the production chain. This rate is lower in the services sector: investments are mostly performed by market-seeking firms.[4]

Why Turkey?

With almost half of its population under the age of 30, Turkey has a young and dynamic labor force. It has a fast-growing economy that registers an average annual growth rate of 5 percent, which also keeps it among countries with a broad market opportunity. The schooling rate reaching 80 percent in secondary education and an average number of 800,000 students graduating from universities each year also indicate that the educational level of the labor force is increasing. By virtue of its geographical location, Turkey is an efficient and cost-effective point of origin with access to important markets and also a significant energy terminal/gate connecting the East and the West.

Arrangements such as the Customs Union and free trade agreements have enabled Turkey’s corporate structure, business routines, consumption patterns, etc. to be recognized by international firms. This, in turn, has expanded Turkey’s export and trade volume. [5] Gradually increasing use of technology expedites the access to international markets, and contributes to the emergence of a corporate, dynamic, and mature private sector.[6]

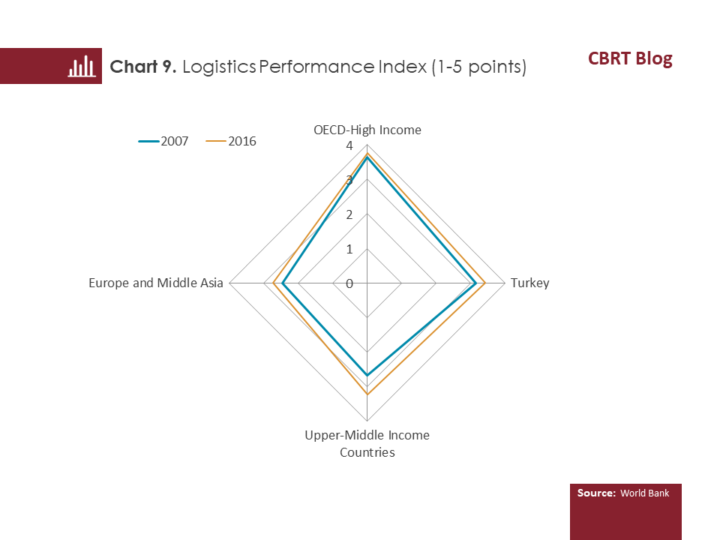

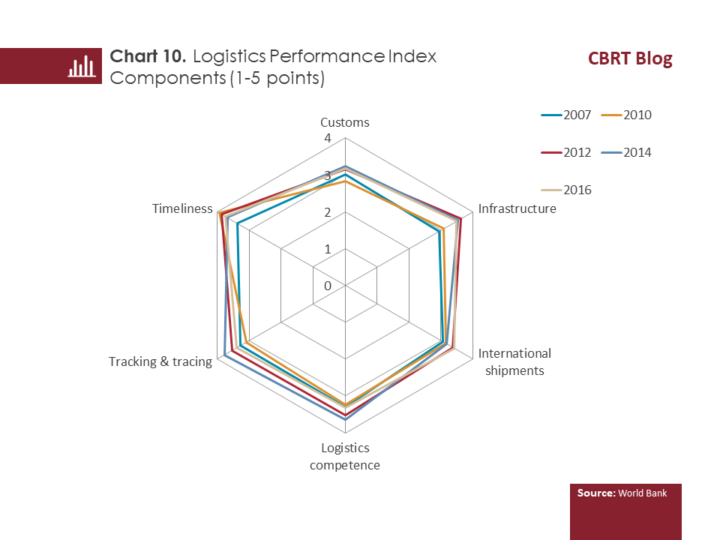

Transport, telecommunications, and energy sectors offer opportunities that facilitate the business environment with new and advanced technical infrastructure. According to the logistics performance index, Turkey has recently made a progress in its infrastructure investments (Chart 9). [7] Nevertheless, it still has a long way to go compared to other high- and middle-income group countries. There are improvements in all sub-sectors of the logistics sector. In particular, the progress in timely completion of infrastructure (road/port/airport) projects and shipment is significant (Chart 10).

Turkey provides profitable investment opportunities for investors through the various support programs it implements. These programs vary depending on coverage areas (general/regional /centers of attraction) and the type of investment (strategic/large-scale/prioritized). Regional incentives are intended to extend the investments across the whole country. Sectors and products to be subsidized have been identified based on the needs of the country, and subsidies for such investments have been provided at the highest rate. The impact of incentive programs on the business environment will be visible in the medium and long term. It is important that these programs are put into effect in a clear and timely manner.

Conclusion and Recommendations

With its labor quality, consumption pattern, demand power, technology skills, geographical location, infrastructure, business routine, and incentives, Turkey is a good alternative for both market-seeking and efficiency-seeking FDIs.

Efficiency-seeking FDIs play an important role in the sustainability of Turkey’s comparative advantage. Economic complexity studies, which measure the capacity of countries to open up to new productive industries, suggest that Turkey’s current production structure is very close to producing advanced products but it should be underpinned by industrial policies to start producing these products in a way that will provide relative superiority (Yıldırım, 2018). Accordingly, in the recent period, prioritized, large-scale, and strategic investment incentives have been introduced in particular to produce highly import-dependent products, reduce production constraints and enhance the production quality. The success of the programs depends on improving education and information-based capital as well as on increasing R&D investments. In this respect, technology development zones, techno-parks, and public-industry-university partnerships, which have recently increased in number, have the potential to create an ecosystem that will encourage R&D studies and attract FDIs.

[1] The “2017/2018 Global Investment Competitiveness Report” (World Bank 2018) is based on the results of the survey conducted with 754 executives of multinational companies that have investments in developing countries. The survey asked investors the question “How important are the following features in your company’s decision to invest in developing countries?”, listed the key factors randomly, and asked investors to put these factors in order of importance.

[2] The required features of local suppliers were listed as the capacity and skills of suppliers, information about availability of local suppliers, and government initiatives for upgrading potential suppliers, in that order. Technology transfers to local suppliers may bring about productivity increases and cost advantages for both the foreign and domestic companies (Pack and Saggi, 2001; Blalock and Gertler, 2008).

[3] Pursuant to Article 3/a of the Law No. 4875 put into effect in 2003, foreign investors are allowed to make direct investments in Turkey, and foreign and domestic investors are subject to equal treatment.

[4] The transport sector, one of the services sub-sectors that attract the highest number of foreign investments, is also the sector with the highest foreign value added. Investors attracted to this sector have a predominant market-seeking motivation but they are more efficiency-seeking relative to the overall services sector. Although foreign investors mostly invest in the food sector under the manufacturing industry, the foreign value added in exports of the food sector is significantly lower than in the overall manufacturing industry. The foreign value added ratio in basic metal and electrical/electronical equipment is well above the general average.

[5]According to TURKSTAT data, exports increased by 84 percent from 2006 to 2017, and reached 157 billion dollars. During the same period, the foreign trade volume soared by approximately 74 percent to more than 390 billion dollars.

[6] Data from the Information and Communication Technologies Authority reveal that the number of mobile phone subscribers doubled from 2006 to 2016 to reach 75 million, and the number of broad band internet subscribers increased to 62 million from 2.8 million. Interbank Card Center data demonstrate that the number of credit and debit card holders rose by approximately 24 percent since 2013, and the number of ATMs increased by 10 percent. Mail order/telephone order transactions and online credit card payments surged by 91 percent from 2013 to 2017.

[7] Data used in the logistics performance index (LPI) calculation are taken from a survey conducted with logistics personnel who are asked about foreign countries they are operating in. A total of 160 countries are listed based on 6 different categories. For comparability reasons, data have been reduced to a single indicator by using standard techniques. The indicator takes a value between 1 and 5, with 1 referring to the worst performance and 5 to the best performance.

Bibliography

lquist, R., Berman, N., Mukherjee, R., & Tesar, L. (2018). Financial constraints, institutions, and foreign ownership (No. w24241). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Blalock, G., & Gertler, P. J. (2008). Welfare gains from foreign direct investment through technology transfer to local suppliers. Journal of International Economics, 74(2), 402-421.

OECD (2003), Checklist for Foreign Direct Investment Incentive Policies, Paris.

Pack, H., & Saggi, K. (2001). Vertical technology transfer via international outsourcing. Journal of Development Economics, 65(2), 389-415.

World Bank (2018). 2017/2018 Global Investment Competitiveness Report: Foreign Investors Perspectives and Policy Implications, Washington.

Yıldırım, M. A. (2018, February). Kompleksite ve Ürün Uzayı Metodolojisiyle Türkiye (Turkey via the Complexity and Product Space Methodology, in Turkish only). Koç University-TUSIAD Economic Research Forum Working Papers (No. 1806). Koc University-TUSIAD Economic Research Forum.