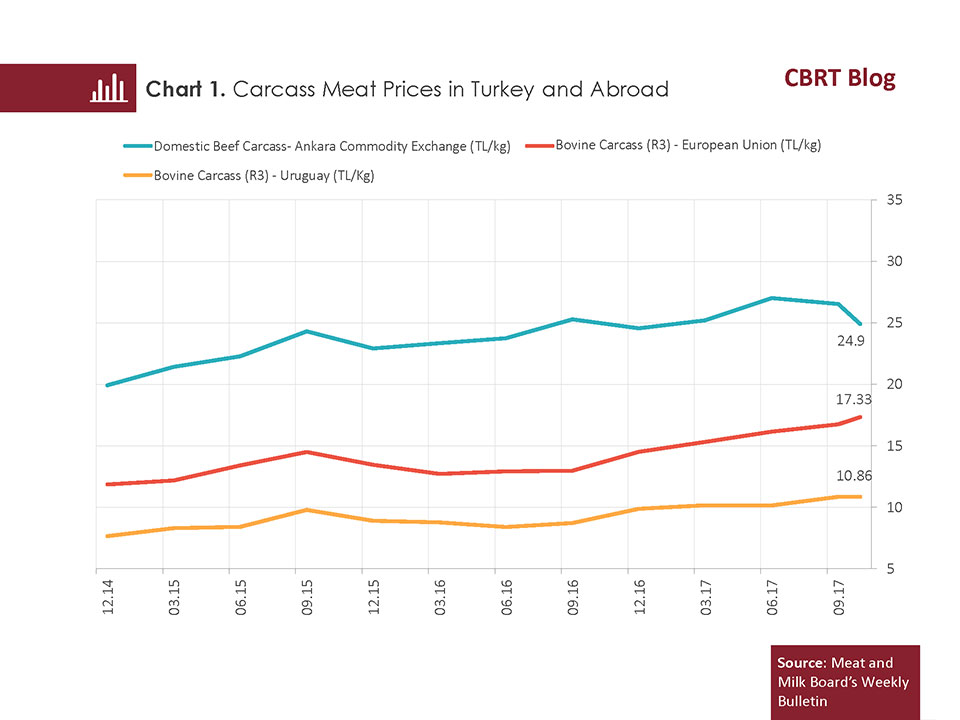

In Turkey, red meat prices are relatively high. In European Union countries, where GDP per capita is higher than in Turkey, the average price of carcass meat is lower than that in Turkey (Chart 1).

This blog post analyzes the factors determining red meat prices, particularly structural pressures on production costs. We will dwell on the importance of feed costs in cattle breeding and livestock fattening and present a detailed analysis of cattle feed by drawing a comparison with grain production and prices.

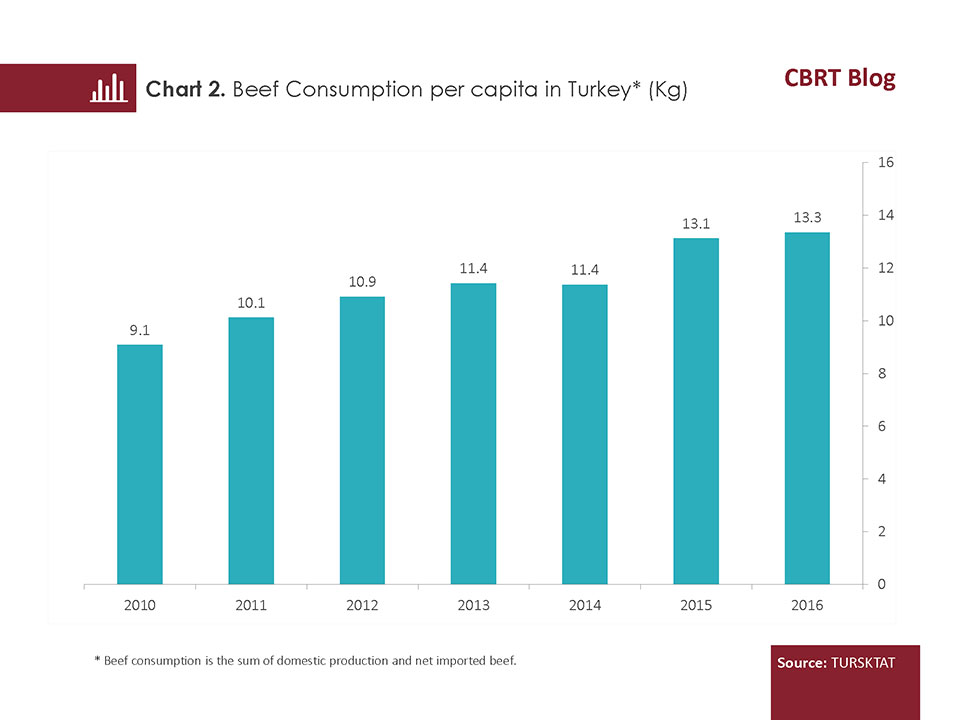

Before moving on to analyzing cattle feed costs in cattle breeding and fattening in Turkey, it would be a good idea to look into beef consumption. Beef consumption per capita in Turkey has been increasing rapidly (Chart 2). This increase is expected to continue in the coming years as consumer’ preferences and habits will likely shift towards beef consumption in tandem with increasing wealth. This prospective change necessitates making medium-long term plans for beef consumption and production.

Carcass beef production is mainly carried out by livestock farms. In cattle breeding terminology, a 12-month calf is called a fatling. Livestock farms either buy 12-month fatlings from farmers in the Eastern Anatolia region and / or import them through the Meat and Milk Board (MMB). Livestock farms rear 12-month fatlings for a period of 6 to 8 months before sending them to slaughter. A breakdown of cost components of carcass beef reveals that 55-60 percent stems from the cost of fatling, 30-35 percent from feed costs, and 10-15 percent from other expenses (labor, financing, medicines, etc.). If the fatling is imported, approximately one third of the cost of carcass beef is composed of domestic feed costs. However, if the livestock farms buy fatlings from the domestic market, than the share of feed costs in the carcass beef cost can reach up to 60 percent because approximately half of fatling cost is composed of feed costs. Therefore, we can assert that feed cost is a very important factor in beef costs.

Two main types of feed are used in cattle breeding and fattening: roughage and mixed feed. Pasturelands, feed plants, silage, grass, straw and stubble are the main feed sources. Among these sources, pasturelands stand out as the cheapest way where the nutritional needs of large animal herds can be met. Nevertheless, Turkey's geography and climate conditions are not very conducive to pastureland breeding and fattening. Pastureland breeding and fattening can only take place in the Northeast Anatolia region and even there, the pastureland season is short. Mixed feed is a fabricated product made up of various grains, oilseed plants, seeds, bran, vitamins and minerals. Primarily, bran products obtained as a byproduct while processing cereal products, cereals and pulses, oilseeds especially soybeans, and pulp obtained as a by-product of processed oilseeds are used in producing mixed feed. As roughage is much cheaper than mixed feeds, countries using roughage incur cheaper costs in cattle rearing. Moreover, major meat exporting countries are those who have ample pastureland.

Mixed feeds are divided into four groups: broiler finisher feed, eggs feed, dairy cattle feed, and fattening feed used in cattle / sheep fattening. The usual ingredients in fattening feed used for cattle fattening are cereal grain products such as barley and corn, corn varieties and bran. Oilseed plants and their pulps are used in fattening feeds to a limited extent and in greater ratios in poultry feeds.

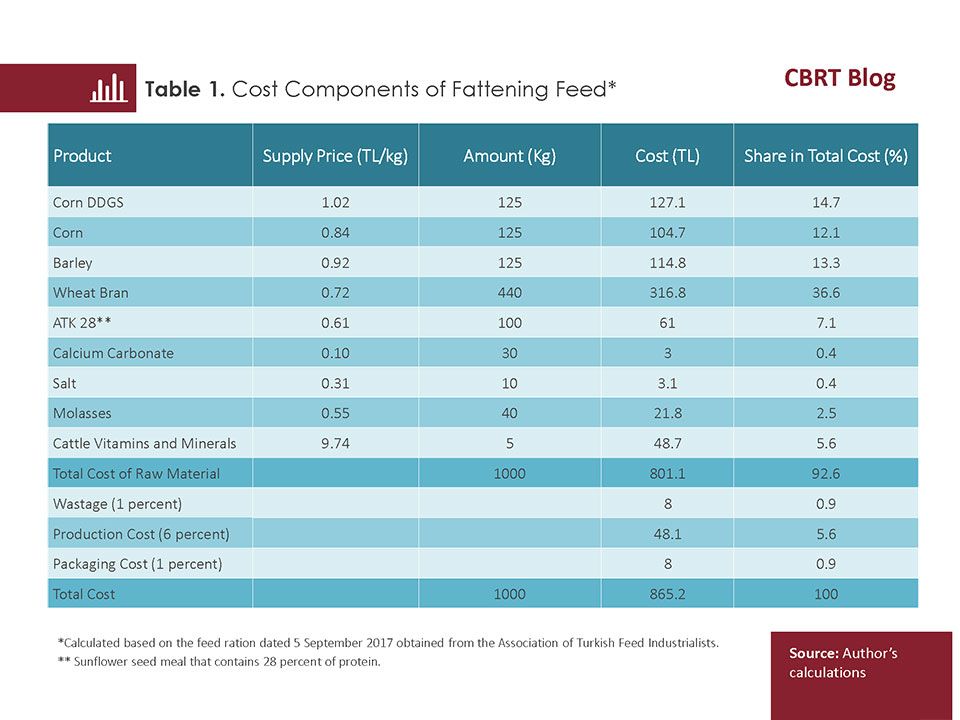

The mixture ratio of feed that meets all the nutritional needs of animals is called the feed ration. Table 1 shows the details of fattening feed costs calculated based on the feed ration study dated 5 September 2017 conducted by the Association of Turkish Feed Industrialists.

While calculating the feed rations, mixed feed producers use a combination of raw materials that provide the lowest price while still meeting the protein and energy content requirements. Therefore, depending on the raw material prices, the composition of the feed ration may change over time. An analysis of the current optimal combination of fattening feeds shows that the share of wheat bran is 36.6 percent, DDNS - a kind of corn by-product- is 14.7 percent, barley is 13.3 percent and corn is 12.1 percent in total cost. We can conclude that the fattening feed is produced using mostly grain products and by-products. While raw materials such as corn DDGS, ATK28, vitamins and minerals are mostly imported, other raw materials are supplied domestically. In this framework, the share of imported raw materials in the total cost of fattening feed raw materials is roughly 30 percent.

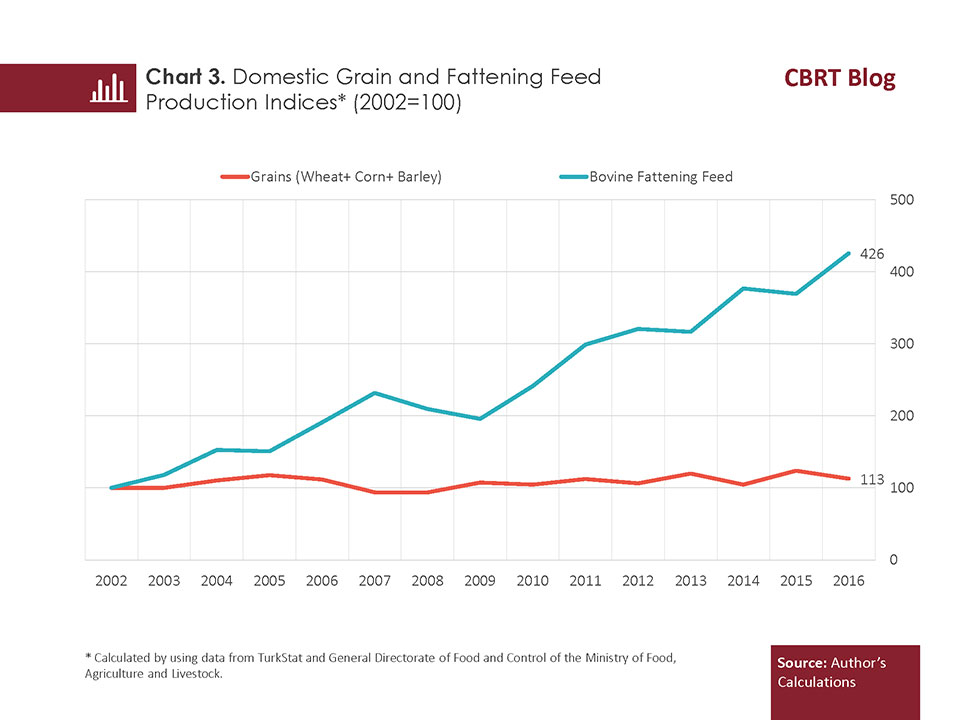

Graph 3 shows our calculations of the development of domestic production quantity indices for grains and mixed feeds. While calculating the quantity index, we used the sum of wheat, corn and barley production. The grains quantity index has increased by only 13 percent since 2002, while mixed feed production in 2016 was almost four times its level in 2002. According to the fattening feed ration dated 5 September 2017, there was 125 kilograms of barley and 125 kilograms of corn in 1 ton of fattening feed. When we assume that the amounts of wheat used in the previous years were the same, we can conclude that 2.2 percent of total barley and corn production was used in producing fattening feed production, and this ratio came as high as 7.3 percent in 2016. Based on this calculation, we can assert that the rapid increase in feed production has exerted a demand-side pressure on grain prices and this pressure tends to increase over time.

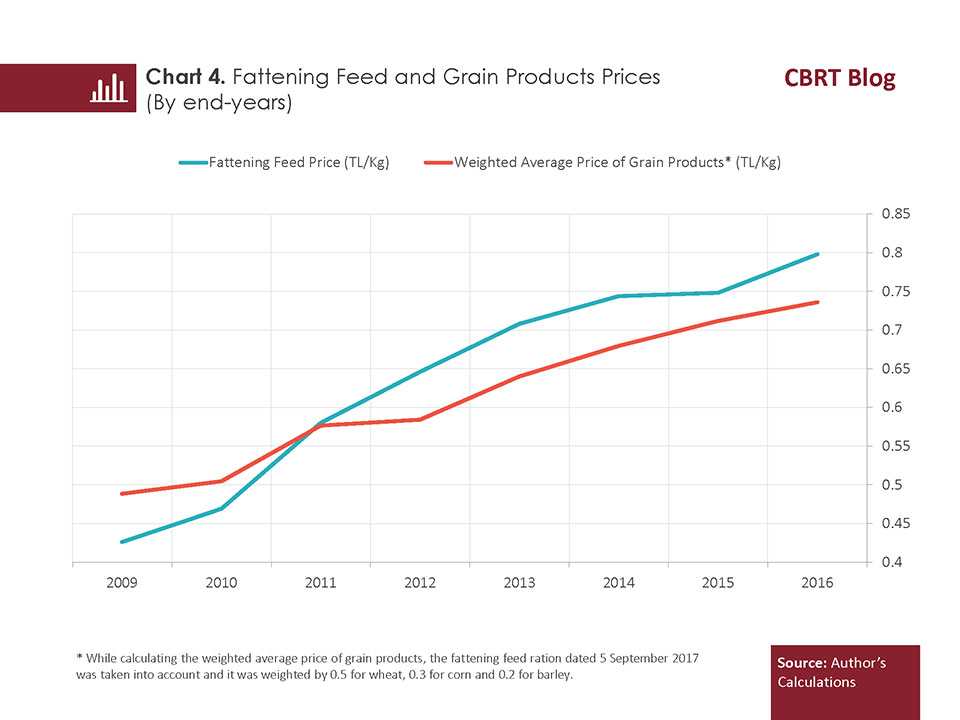

According to the fattening diet ration of 5 September 2017, the share of domestically supplied grains and their by-products in the total raw material cost of fattening feed meal was 67 percent, while the share of imported inputs was 30 percent. We all know that the price of imported inputs in Turkish liras between 2009 and 2016 displayed a significant increase due to the exchange rate effect. When this effect is taken into account, we observe that in this period, the price of feed moved in tandem with the weighted average price of grains (Chart 4).

In Turkey, cereal prices are above global prices due to various structural problems such as low productivity and protectionism. Table 2 shows prices of wheat, barley and corn in Turkey and in international export prices on 13 November 2017. Depending on the type of grain/cereal, domestic prices are 20 to 35 percent more expensive than international export prices.

These observations point to the fact that one of the main causes of high meat prices in our country may be relatively high grains/cereal prices that lead to high feed prices. The fact that cattle rearing in Turkey mostly depends on fattening feed brings about relatively high meat prices.

To summarize, demand for beef in Turkey is increasing, and there is significant pressure on meat production costs stemming from prices of fattening feed. While fattening feed production and consumption increased four-fold over the last 15 years, grain production, which plays a crucial role in the formation of feed prices, stayed almost the same. The rise in the cost of feedstock raw materials was driven by the increase in domestic grain prices stemming from supply and demand as well as by exchange rate developments. As a consequence of all these factors, red meat is more expensive in Turkey than countries with higher GDP per capita.

In November 2017, in line with the decision taken by the Food Committee, the customs tax for various grain brans used as raw material by the mixed feed industry was reduced to zero and customs tax for some oilseed pulps was reduced to 6.5 percent provided that they are to be used in the feed industry. We believe that this decision is an important step towards decreasing production costs. In addition to this decision, the findings of this study suggest that measures to be taken in three key areas would generate significant additional benefits. Firstly, it is important to promote the use of roughage in cattle fattening. In this respect, we believe that reviewing and strengthening livestock breeding policies such as improvement and expansion of pasturelands and increasing production of roughage plants are very important. Secondly, introducing policies that will help Turkish grain prices converge with global prices would enhance predictability of pricing and costs. At this point, it should be borne in mind that increasing productivity in grain production is also very important. Finally, some medium/ long term support and training programs should be developed towards increasing the supply of cattle in Turkey. In this context, it is critical to introduce regional incentive policies as well as measures to increase efficiency and productivity in cattle breeding.